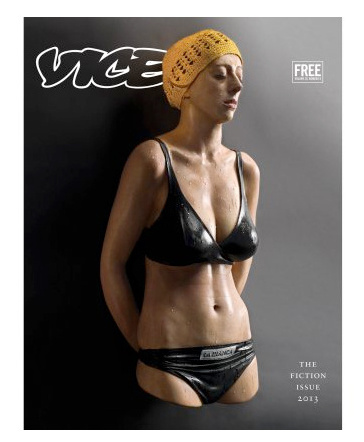

Vice magazine created a shitstorm by publishing a photo spread of models depicted as famous female authors at the moment of their suicides. I’m all for freedom of expression and would never advocate banning such things. But as an art fan I can offer my critique: This spread was utter crap.

Mood music:

Vice pulled the feature down from its site after a public outcry, but the print version is still available and the magazine got the desired attention in the process. That’s what magazines like Vice are all about — doing shocking things for attention. In radio, that’s what shock jocks do. Fine.

But as someone who lost a dear friend to suicide and has watched many good, talented souls lose the battle against depression and insanity, it seems like all we have here is a glorification of brilliant lives gone to waste. The photos include a model portraying Virginia Wolf at the moment she fills her clothes with boulders and drowns herself. The “Last Words” feature also recreated the suicide of Beat poet Elise Cowen, who jumped to her death from the window of a building her parents were living in at the time.

Though the spread has been removed, the photos also appear with an article on the controversy in the publication Jezebel.

When I say this spread was crap, I’m speaking from the perspective of someone who admittedly gets set off about suicide. But that’s a personal opinion. If people want to create this kind of art, that should be their right.

As well, once something is published, the publication ought to stand by it. Pulling the spread was stupid. If you’re not willing to stand by your art, you’re a coward. I offered my critique. Others should be able to do so as well.

I don’t know if there’s a lesson in here. I’m not one to tell people how they should express themselves. That would be hypocritical of me.

As for the question of whether the spread glamorized suicide and possibly inspired future acts of self-demise, I’m not really worried about that. Art depicting that kind of darkness has always been out there. That’s a staple of the heavy metal music I love so much. People may find that kind of art cathartic or they may not. But neither the art or the artist is responsible for what people do because of that art.

Instead of banning art that glorifies suicide, we need to keep coming up with better suicide prevention tools. Fortunately, there’s a lot of activity on that front, including movements in the tech industry to provide suicide prevention training and forums for those experiencing job depression to make sense of their lives and relate to the pain of others.

As long as such prevention and education activities persist, we have a fighting chance to gain an upper hand over depression, even in the face of art that makes suicide look glamorous and cool.