A tale of terror in newsrooms across the state of Massachusetts.

I love my job. I love the subject matter (IT and physical security, emergency preparedness, regulatory compliance). I love the people I work with, many of whom I’ve worked with at other points in my nearly 19 years in journalism. And I love my daily dealings with some of the smartest, passionate security professionals on the planet.

But it wasn’t always this way. Work used to be something to dread, binge eat and get sick over. And I had no one to blame but myself.

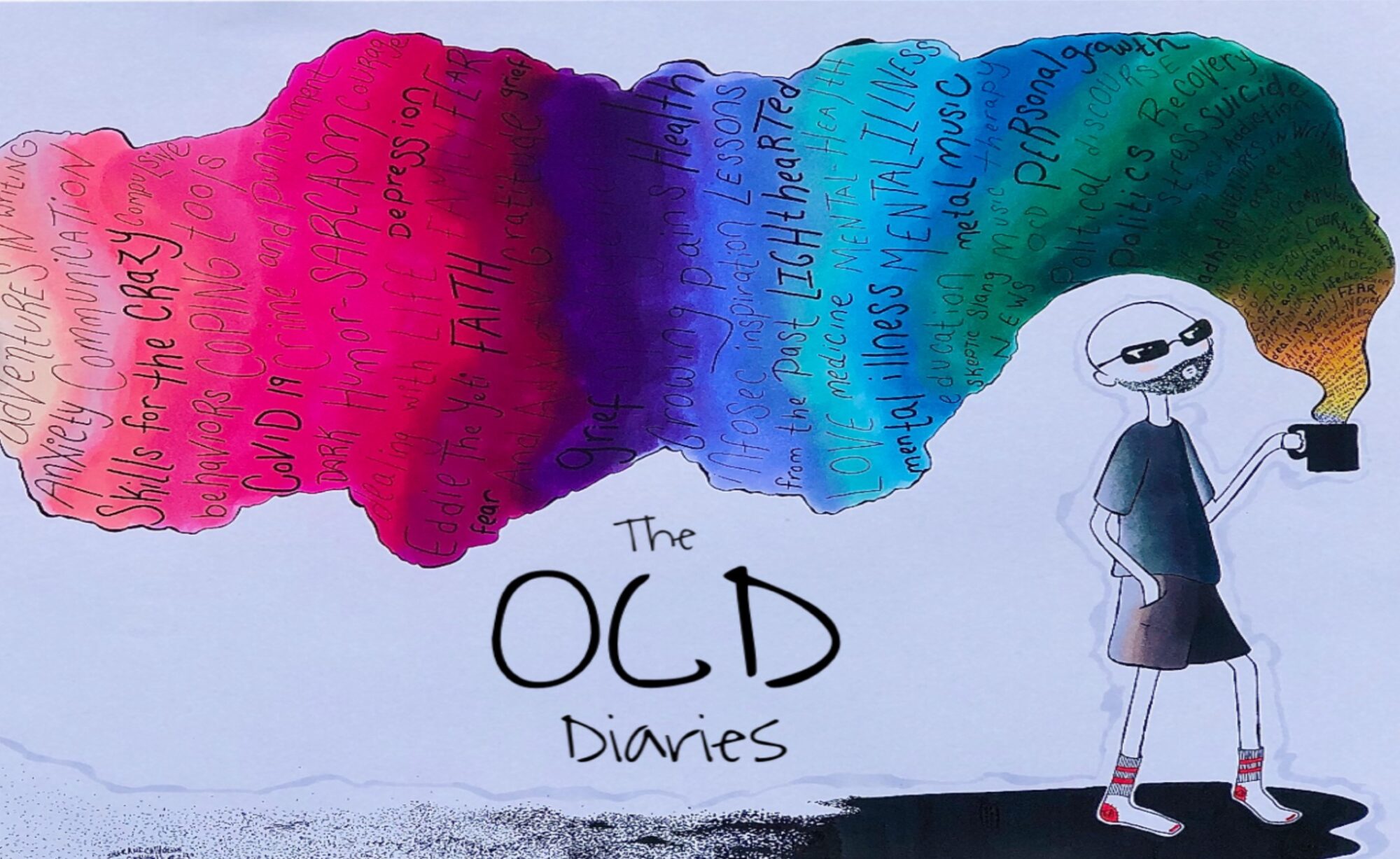

For me, one of the main triggers for obsessive-compulsive behavior was work. I was driven to the brink by a desire to be the golden boy, the guy who worked the most hours, wrote the most stories, handled the most shit work and pleased the most managers.

Golden Boy

I got my first reporting job at Community Newspaper Company, covering the school system in Swampscott, Mass. It was part time, but I put in more than 40 hours a week. Not terrible. I liked the people I worked with and felt pretty dang good about having the job even though I was still one course shy of earning my degree. But I spent much of the time in fear that I wouldn’t measure up. My head would spin at 3 a.m. as I tried to come up with things to write about and prove my worth. My weight soared from 230 pounds — already too much — to 260.

Sullen Boy

The next job was full-time as reporter for the Stoneham Sun. I pretty much worked around the clock, trying to show the editor, managing editor and editor-in-chief (all friends to this day, BTW) that I was THE MAN. Late in my tenure on this beat, my best friend killed himself and I binged as much on work as on food to bury my rage. It didn’t work. I gained another 20 pounds and wrote a column about my friend’s suicide, naming names and describing the method of death in way too much detail. To this day, his parents and sister won’t have anything to do with me, and I can’t say I blame them.

Lynn Sunday Post and Peter Sugarman

This was a bad year. My best friend had just died and I was given the task of editing The Lynn Sunday Post, a newspaper that was on its deathbed. You could say I was chosen to be its pallbearer. There was barely a staff. Few people read it anymore. My only day off was Monday. And my only reporter was an eccentric guy with a cheezy mustache: Peter Sugarman.

He infuriated me from the start, writing epic stories dripping with his personal passion and political agenda instead of the objective writing I was taught to follow in college journalism classes (Peter would call it my J-School side, and it wasn’t a compliment).

It was only natural that he would become my new best friend, another older brother who was always tring to get me to see the light (his way of doing things).

He and his wife Regina were a constant presence from that time until he choked to death in May 2004, three weeks after I started my SearchSecurity job. But while he was around, I learned a lot about using my writing as an agent of change, a force for good, and about thinking about the readers instead of the higher ups I had been trying so desperately to please.

Another person put in the right place at the right time by God.

Interlude

Much of the same behavior while editor of The Billerica Minuteman, though there was some level of stability during this period.

Deep Slide

During this period I was night editor at The Eagle-Tribune.

Before I go further, I should mention that what follows is HOW I SAW THINGS AT THE TIME, NOT NECESSARILY HOW THINGS ACTUALLY WERE.

For a year and a half of that I was assistant editor of the New Hampshire edition. It started off well enough. But this was a tougher environment than I had experienced before. Editors were tougher to please and often at cross purposes with each other. Part of the task I was handed was to be the bad cop that called reporters late at night to rip them over one perceived injustice or another. I sucked at it. I mostly came off as an asshole, and it never made a difference for the better.

The most insidious, bitter part of the experience was during my time on the New Hampshire staff. The managing editor I worked for directly seemed to relish cracking down on reporters, putting them down and ripping their work to shreds. And he expected me to do it the same way, exactly as he did it.

To be fair, the guy wasn’t without a soul. He tried to do the right thing most of the time and genuinely cared about the people under him. But he was also consumed with the idea that all the other editors on staff were out to get us and undermine our efforts. Everyone was a back-stabber. Whenever I had the impulse to collaborate with editors from other sections or let some things slide, he came down hard.

More than ever, I was being the editor he wanted me to be and not who I really was. I called reporters at all hours. I put them down. I fought with other editors and hovered over the page designers on deadline.

I also came as close as I had to an emotional breakdown at that point. I started calling in sick A lot. I’d wake up with the urge to throw up. By mid-afternoon, the urge switched to binge eating.

That managing editor eventually moved on and I returned to the night desk. By then, I was burning out, a shell of the man I once was. By the time I left there, everyone on staff was evil in my eyes; the cause of everything that had gone wrong.

I was wrong for the most part. Fortunately for me, most of my co-workers from the period looked past my insanity and today many of them are among my dearest friends.

Working a Dream Job But Trapped in the Mental House of Horrors

For the next four years I wrote for SearchSecurity.com, part of the TechTarget company. The job was everything I could have hoped for. Excellent colleagues, a ton of creative freedom and plenty of success came my way.

It also coincided with another emotional meltdown as I started to wake up to the mental illness and the fact that I needed to do something about it.

I think I hid it from my colleagues pretty well, except for my direct editor, Ann Saita, who became something of a mom to me, a nurturing soul I could spill my guts to. I’m pretty sure God put her in the right place at the right time, knowing my time of reckoning was at hand. During this period, I untangled all the mental wiring, started taking Prozac (See “The Bad Pill Kept Me from the Good Pill“), officially became a devout Catholic (more on that later) and finally started to feel whole.

Managing Editor, CSO Magazine and beyond

My current job is truly the best I’ve had. I get to work with people like Derek Slater, Joan Goodchild and Jim Malone, who was my editor-in-chief during my first reporting jobs at CNC and one of the folks I went out of my mind trying to please. A side note that amuses me greatly: Peter Sugarman used to drive him nuts, too.

The most noteworthy thing about the last year and a half is that a personal focus has been to get a handle on the eating. In 2008 I discovered OA and started to regain the upper hand. I quit flour and sugar and started putting all my food on a little scale. My mind cleared.

Here’s the best part about my present situation: From Day 1 at CSO, I have not once worried about being a people pleaser. I’ve just focused on the projects I believed in and my bosses have been content to let me have at it.

I don’t work much more than 40 hours a week, and the funny thing is that I’m more prolific now than I ever was before.

Business travel I used to dread has become a joy. Speaking in front of people has gone from something to fear to something to do more of.

Now, five years into my stint at CSO, I’m headed for a new challenge, focusing all my writing and editing skills on the security data at Akamai Technologies. I feel no dread, only happiness and glee.

And to think — All I had to do was get out of my own way.