This week marks a life-altering milestone: Five years since losing my aunt and father a week apart. Both passings were expected. They were terminally ill, their health having declined steadily leading up to that point.

Mood Music:

These five years have been a strange kind of grief. I’ve experienced plenty of that in my life, losing a brother when he was 17 and a best friend to suicide. I’ve experienced more since my father and aunt passed on, especially when my father-in-law died unexpectedly in 2017.

What has made this grief strange is that at the beginning, I had no time to process my feelings. Dad left behind unfinished business — the building that housed the family business for 40 years remained unsold because of a significant environmental cleanup that was just beginning at the time, the result of leaked laundromat chemicals he sold in the 1970s and ’80s.

I was successful in my career and, thankfully, have managed to keep it that way all the while. But in the business world my father excelled at, I was a fish out of water, with no idea of what I was doing.

One thing I have in common with Dad is that I’m a survivor. I’ve aged in recent years, my beard going from mostly black to almost entirely white. I gained a lot of weight and developed myriad health problems before regaining control last year, dropping 80 pounds and developing discipline with food and exercise — just in time to tough out the pandemic. I’ve experienced at least two severe depressions and countless bouts of heavy anxiety in that time.

I’ve failed at things Dad was good at. He knew how to make deals and could be brutally tough with business associates he thought were asking for too much or outright trying to screw him. My tendency to compromise, make everyone happy and be fair have blinded me to some of the human failings my father could smell from a mile away.

I’ve paid the price for that.

I’ve learned much along the way and have taken corrective actions, but as a wise person once said: “Some people get rich. Others get experience.”

I’m finally about to sell the building and the cleanup is in its final stages. But the effort has left a complicated trail of challenges I’ll manage for the foreseeable future.

The things I’ve learned will see me through that. Some of what happens next will come down to a roll of the dice. Fortunately, one lesson from Dad that has stuck with me is that there are no quick solutions. You have to be willing to play the long game.

Tackling these challenges along with doing my real job and being a husband and father has left little time for the kind of grieving I’ve done for so many others — the reflection and tears that are part of the process. My coping mechanisms before finding my way back to fitness were self-destructive.

Maybe I’ll grieve properly by the time we reach the 10th anniversary. For now, there’s a lot I’m grateful for:

I’ve grown and done a lot of cool things in my chosen profession. My wife has branched out with her business in recent years and taken on a lot of challenges that make me proud. My kids have thrived. Both are in honors programs and have excelled in the Boy Scouts (the oldest achieved Eagle rank two years ago, the younger one is well on his way).

My siblings have made me proud by living their best lives — excelling in their own careers and not allowing their grief to crush them.

We’re a resilient family, determined to do good in the world. That will continue.

At one point, obsessed with preserving Dad’s efforts to leave a financial legacy for my sisters and me, I lost sight of something that is now clearer than ever:

That drive and resilience to be a blessing to those around us is Dad’s, and Aunt Marlene’s, true legacy.

Aunt Marlene worked herself to the bone in service to the family business for most of her adult life and lived with my grandmother, taking care of her to the end.

She spent a lot of time caring for us kids as if we were her own children.

Yes, it’ll be a difficult week remembering these two forces in our lives. But I suspect that they are looking down, satisfied that, for all the missteps and moments of difficulty, the thing they held most dear is as sturdy as ever.

The Brenner family endures.

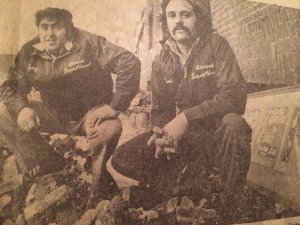

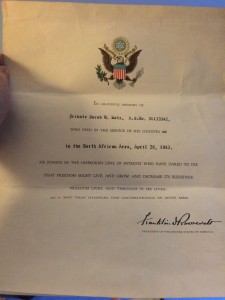

Dad and an employee stand over the rubble of Brenner Paper Company after the 1973 Chelsea fire. Within a year, he had the business back up and running from a new building in Saugus.

Dad and an employee stand over the rubble of Brenner Paper Company after the 1973 Chelsea fire. Within a year, he had the business back up and running from a new building in Saugus.

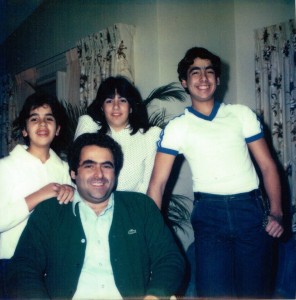

Me with Dad, Wendi and Michael, Christmas Eve 1982.

Me with Dad, Wendi and Michael, Christmas Eve 1982.