I’ve often gone through my career feeling like an impostor.

I work with some ridiculously smart people and know many more in my industry. They seem interested in my opinion on things, and I try to deliver. But many times I don’t know the answer. So I sit wondering how the hell I got here. I know people who can bullshit their way through the answer to a question, but I lack that special talent. So I usually just admit that I don’t know.

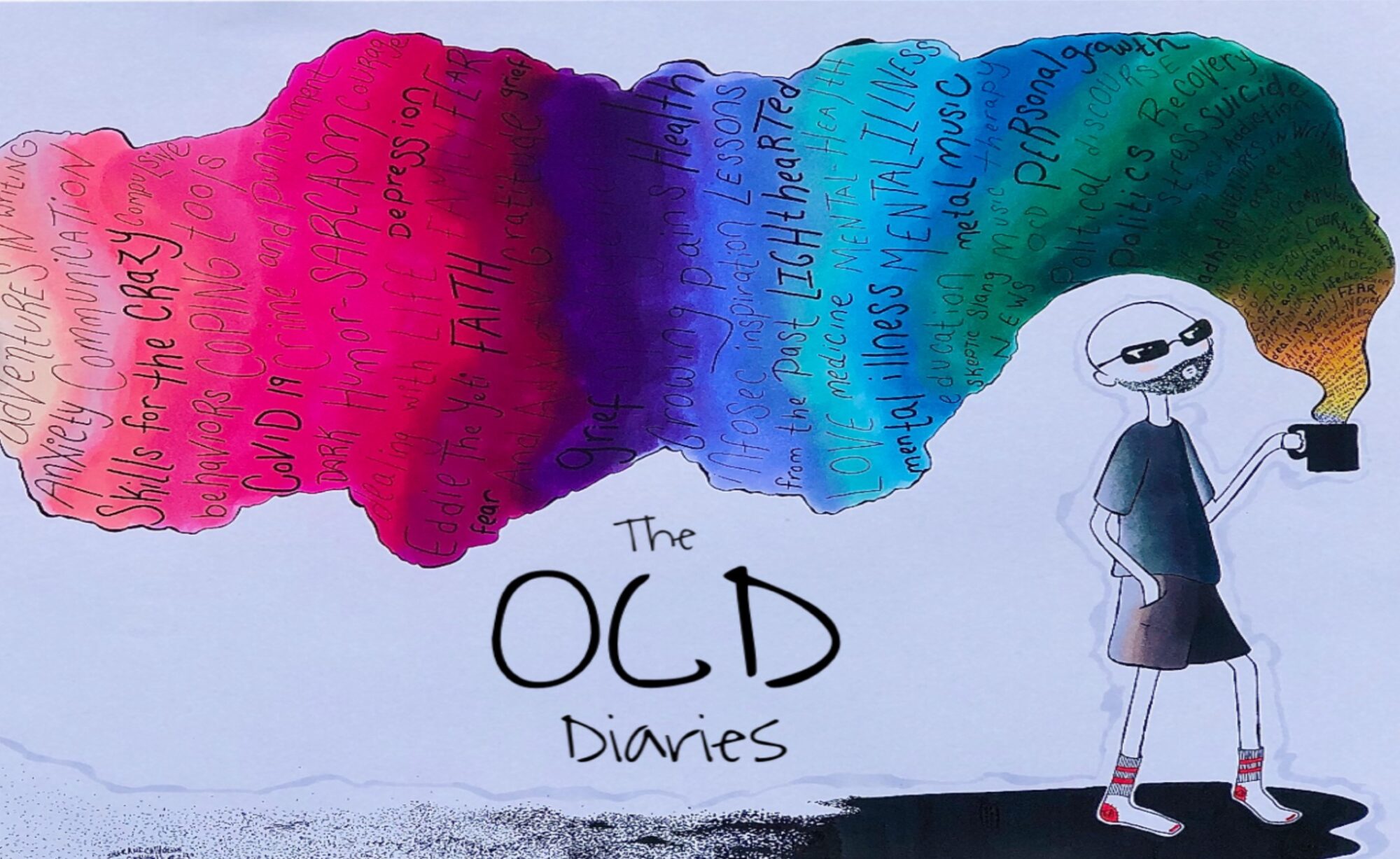

Mood music:

That answer has only led to more good fortune. We think we’ll be dismissed if we admit ignorance, but the smarter folks among us actually appreciate the honesty. When I write about complex security issues in my work blogs, I often admit my befuddlement and open the floor for discussion in an effort to make readers — and myself — more aware of the given topic. In this blog, my frequent admission of ignorance clicks with readers, who find comfort in knowing they’re not the only clueless people on Earth.

The benefits of admitting you don’t know is the focus of a new book, simply titled I Don’t Know by Leah Hager Cohen. I haven’t read it yet, but I have read the essay it’s based on and have listened to her on WBUR, the Boston NPR affiliate.

It’s a refreshing, comforting, even, take on learning to honor one’s doubt. In the essay that started the project, Cohen writes:

Fear engenders lying. If we want our colleges and universities to be bastions of academic integrity, we need to look honestly at the ways they might encourage fakery by stoking fear. In Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Émile: Or, Treatise on Education,” the philosopher writes, “’I do not know’ is a phrase which becomes us.” Too often we fear uttering these words, convinced that doing so will diminish us, will undermine our status and block our advancement.

In fact these words liberate and empower. So much of the condition of being human involves not knowing. The more comfortable we become with this truth, the more fully and unabashedly we may inhabit our skins, our souls, and — speaking of learning — the more able we become to grow.

As someone who used to suffer from crippling fear and anxiety, I get that now. Fear of being diminished in the minds of those you respect makes the lies pour from your mouth before you have time to process what you’re actually saying. Then you’ve made matters worse.

By admitting ignorance from the outset and saying “I don’t know,” you’ll have spared yourself a lot of future pain and indignity and instead set yourself up to become wiser. It’s good to see that point has been articulated in a book.