In recent months, I’ve had a sour attitude. My eating has been erratic, I’ve barely exercised or picked up the guitar, and I have far less patience for people than usual. I’ve come to realize the reason.

I haven’t really been dealing with the emotional scar of losing my father last year.

Mood music:

https://youtu.be/Dd4Uto-0XZg?list=RDDd4Uto-0XZg

I thought I was. I dove headfirst into the task of untangling his unfinished business interests, specifically managing the building that housed the family business for more than 40 years. It fell to me to manage the trusts associated with it, and there’s been a costly chemical spill cleanup to pay for and oversee.

After several failed attempts to sell the building, I decided to lease it out until the clean-up is done, fix the place up and then sell it in a few years. I brought someone in to manage the building for me, and we’re finally making some much-needed repairs.

Thankfully, I’ve been able to keep putting 100% into my real job, earning a “consistently exceeds expectations” on my last performance review. During the review period, I threw myself into a new role in the company while keeping vigil in my father’s hospice room, dealing with two other family deaths within the same three-week period and, as mentioned, taking the reigns of the Brenner business.

But some things have suffered. In addition to the lack of guitar playing, I haven’t been writing in this blog nearly as much as I should. I’ve been too busy and tired. And I’ve been neglecting other people. I’ve been carrying around a “fuck you” attitude that rivals that of my teens and early 20s, which is saying something.

For a long time, I thought all these things were the result of grieving for my father. But as I’ve heard other family members talk about their own grieving processes, I realize I simply threw myself into all that work, too overwhelmed with the responsibilities to have the luxury to grieve.

Funny that, given everything I’ve written about managing grief.

I’ve had far less empathy and patience for other family members. I think some of that is because I’m jealous of their ability to grieve. I haven’t been able to do any personal travels to contemplate the last year. I haven’t been able to drop a single tear.

Some of it is because I can’t put him on a pedestal the way they can. I’ve spent a lot of time being angry and resentful of the old man for dumping this mess on my shoulders.

To keep doing my real job with all the time and energy it deserves while keeping a closer eye on the building, I moved into my father’s office. His fishing pictures, hanging stuffed sailfish and scattered piles of paperwork have been replaced with my own family portraits and some guitar- and movie-oriented wall hangings. The filing cabinets have an increasing array of stickers about hacking, a nod to my work in infosec.

Sometimes I sit there and remember hanging out in this office as he worked, and it makes me a little sad. It definitely makes me think of the strange turn my life has taken this past year. Never in a trillion years did I ever expect to be occupying that office for my own work.

The logical question is what I’m going to do to start grieving properly. Honestly, I’m not sure.

I know I have to start taking better care of myself. I have to start using my mental coping tools to their full power again. I know I need to start being more patient with people.

I’m still feeling things out in this journey. Maybe acknowledging the problem is the first step toward a solution.

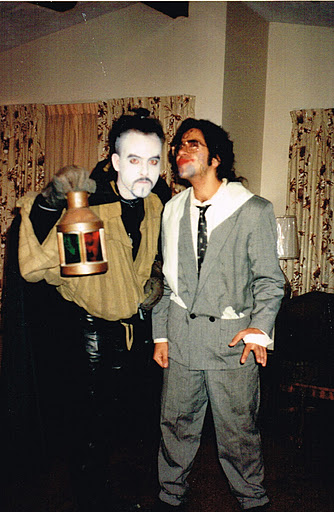

Sean Marley and me, Halloween 1990.

Sean Marley and me, Halloween 1990.