My 12-year-old has a few things in common with his dad. Both of us have mental disorders (his is ADHD, mine is OCD with wintertime undercurrents of ADHD). Both of us take medication to help manage our ills. But until last weekend, he had never asked the big question:

“What do these pills do, anyway?”

Mood music:

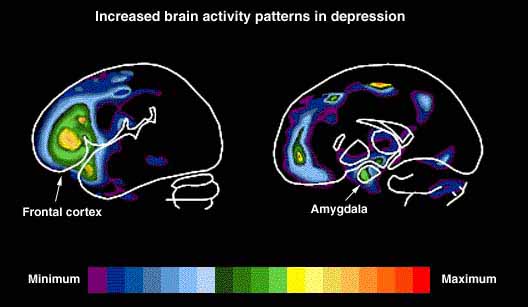

To answer the question, I dusted off an analogy I had used some years ago to explain it to others. Essentially, I told him, the brain is an engine. When one part gets worn out, the whole the engine can fail. An engine needs the right amount of oil, transmission fluid, brake fluid, and so forth to function properly.

If the oil runs out, for example, the engine seizes up. If the brake fluid runs dry, the breaks fail. Too much of these fluids can harm the engine, as well.

Car owners and auto mechanics use many different techniques to keep engines healthy or fix them when they break. It could be something simple, like topping off the oil, to something more complex, like realigning or replacing faulty parts.

The brain works much the same way.

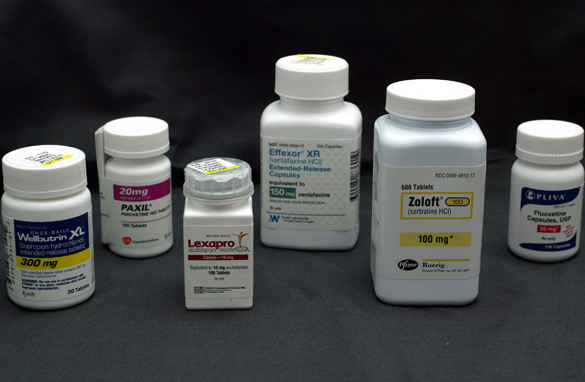

Think of a psychotherapist as the auto mechanic who is well versed in how to regulate the different engine fluids and pinpoint specific fixes for specific problems.

The different drugs are tools the mechanic uses to deal with specific problems in the engine. In the brain, when certain fluids are running low, the result is depression and a host of other mental disorders.

In my case, Prozac addresses the very specific fluid deficiencies that spark OCD behavior. Since OCD is essentially the brain pumping and spinning out of control, I like to think of my specific problem as a lack of brake fluid.

When I explained it this way, I think he got it.