Remembering Peter Sugarman, another adopted brother who died too early — but not before teaching the author some important lessons about life.

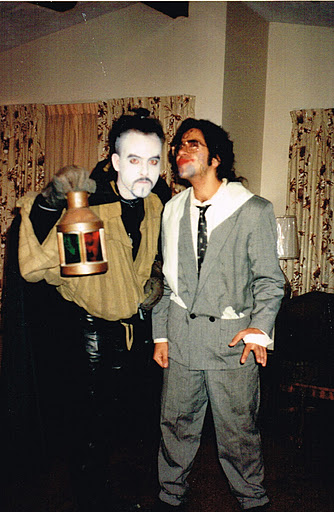

The first time I met him was my second day as a reporter for The Stoneham Sun. He was an oddball who wore a jacket and tie to go with his sneakers and sweatpants. He was rail thin with a mustache that could comfortably hide a pound of whatever crumbs got caught there.

He wore a a strange-looking hat over a thick mop of hair. I was absolutely certain from Day 1 that the hair was fake, but never asked about it.

This is the tale of Peter Sugarman, another older brother who left me before I was ready. But he taught me some important lessons along the way and — oddly enough — his death was the catalyst for me finally getting the help I needed for what eventually became an OCD diagnosis.

My friendship with Peter really blossomed over the course of 1997, though it was a year earlier when I had first met him. I was in a bad place. My best friend, Sean Marley, had recently died and I had just taken a job as editor of the Lynn Sunday Post, a publication that was doomed long before I got there. I just didn’t realize it when I took the job.

I worked 80 hours a week. To get through the pressure I binge ate like never before and isolated myself. I had no real friends at the time because no one could compete with a dark room and a TV clicker.

But Peter was a bright spot, even though he was infuriating my editor side. A lot. His writing could be off the wall and opinionated when I was looking for straight, objective articles from him.

He once wrote about a blind man who, instead of offering a story of inspiration and living large in the face of adversity, led a bitter existence and talked about that bitterness during his interview with Peter. I opened the story on my screen for editing and saw the headline “Blind Man’s No Bluff.” I let the headline go to print, though I shouldn’t have. But the dark side in me thought it was funny, and the higher ups weren’t paying enough attention to The Post to notice.

He would write one story after the next questioning the motives of city councilors and the mayor. He would tag along with firefighters and write glowing narratives portraying them as heroes. That would have been fine if the assigned piece called for opinion. But it didn’t, and I edited it heavily.

That Sunday, I found a voicemail from Peter. He was furious, ripping into me for letting the J-School in me take over and ruin a perfectly good piece of journalistic brilliance.

I quickly got used to getting those messages every Sunday.

At the same time, we became constant companions. Whenever I left my dark bedroom, it was either to be with Erin, by then my fiance, or Peter. We hung out in every coffee shop in Lynn. He showed me the dangerous neighborhoods, introduced me to the city’s most colorful characters and showed me hidden gems like the Lynn Historical Society, where I was treated to boxes of old correspondence from former Mass. Speaker Tommy McGee, a colorful pol who, like many a Speaker who followed, eventually left the Statehouse under a cloud of corruption. I wrote about the old correspondence and interviewed McGee in his Danvers condominium. I couldn’t help but like the guy.

Peter and his wife, Regina, became constant dinner companions. When I finally escaped from The Post, our friendship deepened. I still hired him for the occasional freelance article in the Billerica paper I was editing. He would show up to cover meetings wearing his colorful collection of hats, including one that had “Yellow Journalist” emblazoned across the front.

He became my favorite person to talk politics with. He was at every family gathering. He and Regina were a constant presence when both our children entered the world. They were at every kid’s birthday party. They were here for our Christmas Eve parties.

Peter was in bad health, though, and was often in the hospital. His colon had been removed long before I met him and he continued to smoke. He was also a ball of stress when traditional J-School editors were tampering with his writing. I would call him and he would rage at whoever the editor was at that moment.

I enjoyed the hell out of it. His tirades always entertained me, whether I was the target or not.

I ultimately came to understood what it was all about. He wasn’t in journalism to write the traditional reports people like me were taught to write. He was in it to root out the truth and help the disadvantaged. He was a man on a mission to right the wrongs he saw. And he did so cheerfully. Even when his temper flared, there was a certain cheerfulness about it.

In the spring of 2004, he developed shingles. He grew depressed, though not beaten by any stretch. Regina later told me he was “bolting” down his food. Swallowing quickly without chewing because the shingles had irritated the heck out of his mouth and throat.

One night, he choked on a piece of chicken. He lost his breath just long enough to cause insurmountable brain damage.

He lingered for about a week in the hospital, essentially dead but still breathing with the aid of life support. For the first time in our friendship, I saw what he looked like without the hairpiece. I was right all along.

In the months following his death, I really started to come unhinged. The OCD took over everything. Fear and anxiety were constant companions.

I finally reached the deep depth I needed to realize I needed help. In the years that followed, I got it. It hasn’t been easy, but then I can always remember that things weren’t easy for Peter. And yet, he carried on with that warped cheerfulness of his.

I’ve endeavored to do the same. I’ve also come to understand the value of the writing he tried to do, and have embraced it.

Thanks, Peter.