The author discovers that winter makes his depression worse and that there’s a purely scientific explanation — and solution.

My therapist and I recently agreed that my Prozac intake should go up a bit for the duration of the winter.

I’m doing well for the most part, but there’s a three-hour window of each day — usually late afternoon — where my mood slides straight into the crapper.

The reason is simple: People who suffer from chemical imbalances in the brain are directly impacted by daylight levels. When the weather is dismal, cold, rainy and the days are shorter, a lot of folks with mental illness find themselves more depressed and moody. Give us a long stretch of dry, sunny weather and days where it gets light at 4:30 a.m. and stays that way past 8 p.m. and we tend to be happier people.

There are lessons to be had in the history books:

— Abraham Lincoln, a man who suffered from deep depression for most of his adult life, went from blue to downright suicidal a few times in the 1840s during long stretches of chilly, rainy weather. [See Why “Lincoln’s Melancholy” is a Must-Read.]

— Ronald Reagan, a sunny personality by most accounts, was a man of Sunny California. Once, upon noticing that his appointments secretary hadn’t worked time in his schedule for trips to his ranch atop the sun-soaked mountains of Southern California — and after the secretary explained that there was a growing public perception that he was spending too much time away from Washington — Reagan handed him back the schedule and ordered that ranch time be worked in. The more trips to the ranch, he explained, the longer he’ll live.

The WebMD site has excellent information on winter depression. Here’s an excerpt:

If your mood gets worse as the weather gets chillier and the days get shorter, you may have “winter depression.” Here, questions to ask your doctor if winter is the saddest season for you.

Why do I seem to get so gloomy each winter, or sometimes beginning in the fall?

You may have what’s called seasonal affective disorder, or SAD. The condition is marked by the onset of depression during the late fall and early winter months, when less natural sunlight is available. It’s thought to occur when daily body rhythms become out-of-sync because of the reduced sunlight.

Some people have depression year round that gets worse in the winter; others have SAD alone, struggling with low moods only in the cooler, darker months. (In a much smaller group of people, the depression occurs in the summer months.)

SAD affects up to 3% of the U.S. population, or about 9 million people, some experts say, and countless others have milder forms of the winter doldrums.

So this worsening of mood in the fall and winter is not just my imagination?

Not at all. This “winter depression” was first identified by a team of researchers at the National Institute of Mental Health in 1984. They found this tendency to have seasonal mood and behavior changes occurs in different degrees, sometimes with mild changes and other times severe mood shifts.

Symptoms can include:

- Sleeping too much

- Experiencing fatigue in the daytime

- Gaining weight

- Having decreased interest in social activities and sex

SAD is more common for residents in northern latitudes. It’s less likely in Florida, for instance, than in New Hampshire. Women are more likely than men to suffer, perhaps because of hormonal factors. In women, SAD becomes less common after menopause.

Here’s where the Prozac comes in for me:

As I mentioned in The Bad Pill Kept Me from the Good Pill, Prozac helps to sustain my brain chemistry at healthy levels. Here’s a more scientific description of how it works from WebMD:

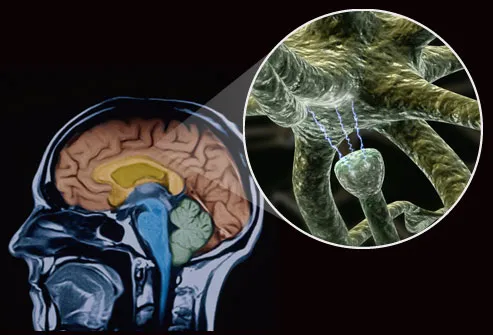

How Antidepressants Work

Most antidepressants work by changing the balance of brain chemicals called neurotransmitters. In people with depression, these chemicals are not used properly by the brain. Antidepressants make the chemicals more available to brain cells like the one shown on the right side of this slide:

Antidepressants can be prescribed by primary care physicians, but people with severe symptoms are usually referred to a psychiatrist.

Realistic Expectations

In general, antidepressants are highly effective, especially when used along with psychotherapy. (The combination has proven to be the most effective treatment for depression.) Most people on antidepressants report eventual improvements in symptoms such as sadness, loss of interest, and hopelessness.

But these drugs do not work right away. It may take one to three weeks before you start to feel better and even longer before you feel the full benefit.

I’m convinced the drug would NOT have worked as well for me had it not been for all the intense therapy I had first. Developing the coping mechanisms had to come first.

I’ve also learned that the medication must be monitored and managed carefully. The levels have to be adjusted at certain times of year — for me, anyway.

So next week I’ll start taking the higher dosage and let y’all know how it goes.