I’ve written a lot about my old friend Sean Marley in this blog. Some of you may be sick of it, but I really have no choice. His death is too intertwined with my own struggles to avoid it. Today is the 14th anniversary of his death, and I’ve learned a lot of painful lessons since then.

Mood music:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwPaMQ-3mFo&fs=1&hl=en_US]

In the weeks leading up to his suicide, I knew he was badly depressed. I even had a feeling he harbored suicidal thoughts. I just never thought he’d do it. Or it could be that I thought I had more time to be there and help him through it. Instead, I stayed wrapped in my own world as he deteriorated.

On Nov. 15, 1996, he decided he’d had enough. It was a sparkling, autumn Friday and I was having a great morning at work. But early that afternoon, I got a call at work from my mother. She had driven by Sean’s house and saw police cars and ambulances and all kinds of commotion on the front lawn. I called his sister and she put his wife on the phone. She informed me he was dead. By his own hand.

He introduced me to metal music, taught me to love life, and his death has been one of the cattle prods for my writing this blog.

I had known Sean for as long as I could remember. He lived two doors down from me on the Lynnway in Revere, Mass. He was always hanging around with my older brother, which is one of the reasons we didn’t hit it off at first.

Friends of older siblings often pick on the younger siblings. I’ve done it. It happens.

Sean always seemed quiet and scholarly to me. By the early 1980s he was starting to grow his hair long and he wore those skinny black leather ties when he had to suit up.

On Jan. 7, 1984 — the day my older brother died — my relationship with Sean began to change. Quickly. I’d like to believe we were both leaning on each other to get through the grief. But the truth of it is that it was just me leaning on him.

He tolerated it. He started introducing me to Motley Crue, Ozzy Osbourne, Van Halen and other hard-boiled music. I think he enjoyed having someone younger around to influence.

As the 1980s progressed, a deep, genuine friendship blossomed. He had indeed become another older brother. I grew my hair long. I started listening to all the heavy metal I could get my hands on. Good thing, too. That music was an outlet for all my teenage rage, keeping me from acting on that rage in ways that almost certainly would have led to trouble.

We did everything together: Drank, got high, went on road trips, including one to California in 1991 where we flew into San Francisco, rented a car and drove around the entire state for 10 days, sleeping and eating in the car.

This was before I became self aware that I had a problem with obsessive-compulsive behavior, fear and anxiety. But the fear was evident on that trip. I was afraid to go to clubs at night for fear we might get mugged. When we drove over the Bay Bridge I was terrified that an earthquake MIGHT strike and the bridge would collapse from beneath us.

I occupied the entire basement apartment of my father’s house, and we had a lot of wild parties there. Sean was a constant presence. His friends became my friends. His cousin became my cousin. I still feel that way about these people today. They are back in my life through Facebook, and I’m grateful for it.

There is a hero in this story, and that’s his wife, Joy. She was there with him day and night, holding him through every agonizing moment. She did everything to keep his spirits up. It didn’t work in the end, but she did her best.

I first met Joy 19 years ago. Sean had just severed what I thought was a poisonous relationship, and when he told me he was seeing this girl Joy, my eyes rolled into the back of my head. Here we go, I thought: Another fucked-up pairing.

It was nothing of the sort.

From the moment I met her, Joy was true to her name. She always made you feel good about yourself and treated you like an old friend even if she didn’t really know you.

She married Sean in 1994, knowing he had a sickness brewing inside. It didn’t matter. Love won out. I was best man, though they could have done far better with someone else in that role.

I was so self-absorbed that day, obsessing about the toast the best man is supposed to give, that I forgot the glass of champagne. The room stared back at me, puzzled. It was more of a speech than a toast, and a bad one at that.

I didn’t trick out their car with the “Just Married” stuff, either.

Fast-forward to the present. Thankfully, Joy found someone else to love and remarried. She has three kids and you can tell how much love she pours into them.

Her parents knew what they were doing when they picked that name.

Thank you, Joy.

The months following Sean’s death were among the worst of my life. I started binge-eating with vicious abandon, and just hated myself. I wrote a column about his death in the paper I wrote for at the time, and I left all the actual names in there. His mother and sister haven’t spoken to me since then. I can’t say I blame them.

I think I had to go through my own depression, mental breakdowns and addiction to understand what was going on in his soul.

Suicide is a tough concept for a Catholic like me. But I’ve learned a few things along the way:

–Blaming yourself is pointless. No matter how many times you replay events in your mind, the fact is that it’s not your fault. For one thing, it’s impossible to get into the head of someone who is contemplating suicide. Sure, there are signs, but since we all get the blues sometimes, it’s very easy to dismiss the signs as something close to normal. When someone is loud in contemplating suicide, it’s usually a cry for help. When the depressed says nothing and even appears OK, it’s usually because they’ve made their decision and are in the quiet, planning stages.

–Blaming each other is even more pointless. Take it from me: Nerves in your circle of family and friends are so raw right now that it won’t take much for relationships to snap into pieces. A week after my friend’s death I wrote a column about it, revealing what in hindsight was too much detail. His family was furious and most of them haven’t talked to me since. They feel I was exploiting his death to advance my writing career and get attention. I was pretty screwed up back then, so they’re probably right. In any event, I don’t blame them for hating me. What I’ve learned, and this is tough to admit, is that you’re going to have to let it go when the finger pointing starts. It’s better not to engage the other side. Nobody is in their right mind at this point, so go easy on each other. Give people space to make their errors in judgment and learn from it.

–Don’t demonize the dead. When a friend takes their life, one of the things that gnaws at the survivors is the notion that — if there is a Heaven and Hell — those who kill themselves are doomed to the latter. I’m a devout Catholic, so you can bet your ass this one has gone through my mind. What I’ve learned though, through my own experiences in the years since, is that depression is a clinical disease. When you are mentally ill, your brain isn’t firing on all thrusters. You engage in self-destructive behavior even though you understand the consequences. A person thinking about suicide is not operating on a sane, normally-functioning mind. So to demonize someone for taking their own life is pointless. To demonize the person, you have to assume they were in their right mind at the time of the act. And you know they weren’t. My practice today is to simply pray for those people, that their souls will still be redeemed and they will know peace. It’s really the best you can do.

– Break the stigma. One of the friends left behind in this latest tragedy has already done something that honors her friend’s life: She went on Facebook and directed people toward the American Association of Suicidology website, specifically the page on knowing the warning signs. That’s a great example of doing something to honor your friend’s memory instead of sitting around second guessing yourself. The best thing to do now is educate people on the disease so that sufferers can help themselves and friends and family can really be of service.

–On with your own life. Nobody will blame you for not being yourself for awhile. You have, after all, just experienced one of the worst tragedies there is. But try not to let it paralyze you. Life must go on. You have to get on with your work and be there for those around you.

Life can be a brutal thing. But it IS a beautiful thing.

Seize it.

It was nothing of the sort.

It was nothing of the sort.

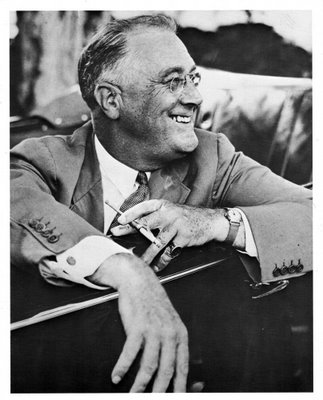

In private, however, he had a lot of pain. Polio had taken away his freedom of movement. He put on a good act in public, using a cane, leg braces and the arm of one of his sons to make it look like he was standing and walking without effort. The truth is that those were moments of blinding physical pain. But he kept the sunny disposition and it was just what people needed at the height of the Great Depression.

In private, however, he had a lot of pain. Polio had taken away his freedom of movement. He put on a good act in public, using a cane, leg braces and the arm of one of his sons to make it look like he was standing and walking without effort. The truth is that those were moments of blinding physical pain. But he kept the sunny disposition and it was just what people needed at the height of the Great Depression.